- Home

- Categories

- Uncategorized

- In realtà anche io sono contrario ai limiti a 30.

In realtà anche io sono contrario ai limiti a 30.

-

In realtà anche io sono contrario ai limiti a 30. Vanno proprio vietate le macchine se non per disabili e mezzi di soccorso

https://flipboard.com/@ilpost/news-6pgniha4z/-/a-ARpE-tEZR46cCKLzGdBqYQ%3Aa%3A2183656918-%2F0

Gli ultimi otto messaggi ricevuti dalla Federazione

-

-

🔎 Ransomware and AI: the new tooling loop

From psychology to automation, our latest report shows how 90%+ of new #ransomware builds are AI-assisted - not AI-made.

Humans still write the strategy, machines just scale it.🔗 read and share the report: https://ransomnews.online/RedACT/RedACTinsights_Ransomware_and_AI.pdf

-

@swart @evan@photos.cosocial.ca it was, but I did get to have them experience of thinking, what in this room do I need to take with me? I grabbed my computer and my journal. It was a good exercise!

-

@emoji__polls it's a joy. Last question: have you tried any of the server-side bot frameworks? @smallcircles has a good list https://delightful.coding.social/delightful-fediverse-development/#frameworks

-

@evan @evan@photos.cosocial.ca aw that’s a drag. I hope it was a false alarm

-

Rodrigo Nunes, in his article From the Organizational Point of View: Bogdanov and the Augustinian Left, introduces a fundamental concept stemming from his long work of weaving together political theory and system theories such as tektology and cybernetics. He calls it: the Augustinian Left.

Let's try to understand what he means. The core argument goes something like this: there are two approaches to understand social and political change; the first approach sees the forces of progress opposed to the forces of reaction, and we call them “Manichean”; the second approach, the Augustinian approach, sees a shared struggle of social forces trying to construct a liberating order in a world of chaos, with the forces of reaction and the forms of oppressive power being simply a symptom of chaos.

The Manicheans understand themselves as a force actively constructing liberation pitted against a force actively constructing oppression: who wins determines the social structure. Good vs Evil.

The Augustinians, instead, see their work as an endless endeavour of organizing chaos into order, with chaos here being a cosmic force akin to entropy, which is an intrinsic and ineliminable trait of the universe we live in that is also reflected in social, productive, political, and cultural structures. Good within Evil.

Obviously, Nunes is Augustinian and provides compelling arguments throughout his work for the necessity of an Augustinian approach. The Manicheans are portrayed as wojaks, and the Augustinians are the chads. I'm an Augustinian too, so I won't pretend my description of the two sides is unbiased. I'm also portraying myself as a chad in the process.

Nunes is very demure, so he tries to connect and appeal to his crowd of Manicheans, raised by a Manichean world, with only that perspective as part of their political toolbox. The change to align with this new grammar of politics, though, is very radical and has the potential to invalidate the vast majority of the political strategies and practices of the Western Left. Not only that, but the very identity of the Left is incompatible with the new frame.

If there are no sides, what does it mean to be “Left”?

As somebody who has employed this system-oriented perspective on politics for several years now, first naively and then more consciously after reading Neither Vertical Nor Horizontal by Nunes, I lived this problem of identity, language, and perspective for a long time, trying to translate and adapt Augustinian ideas and practices for a mostly Manichean crowd, without soliciting a hostile reaction.

Over the years, I came to realize one of the hinges on which this difference is built is a criminally underscrutinized mind-virus. I'm talking about Geometry.

The language of Manichean politics is haunted by Geometry, inheriting concepts, words, and metaphors from the vocabulary of 16th/17th/18th-century war strategy, which was all about geometry. For the Enlightenment generals, the map was the battlefield, and armies were just machines executing orders described by position, orientation, distance, or frequency. You had fronts and sides. You had flanks. You had parties, taking part in a conflict. You had battles, which led to either victory or defeat.

On top of that, in politics, we also inherit the Latin vocabulary of state diplomacy, often articulating military agreements: federations, coalitions, allies. Even the term “society” derives from socius, which was used to describe, among other things, military allies. We are defined by whom we fight against.

Going back to Geometry, we can easily see how we relate to other political entities by imagining and implying a two-dimensional space of politics: “we are distant on this issue”, or “we should build a common front against them”. We try to be the “radical flank”, or “align with others”.

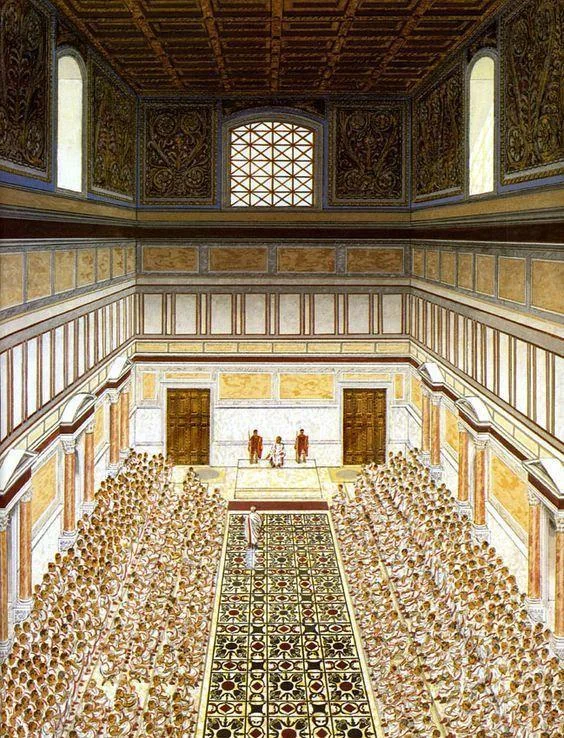

Also, the terminology of “Left” and “Right” is famously derived from the seating arrangements of aristocrats and republicans in the French Revolutionary Parliaments and Assemblies. Those people, imbued with a specific idea of politics, were part of a long tradition of aisle-based (like the Curia Julia) or semi-circular seating arrangements dating back at least to the Roman Senate and Greek citizen assemblies. The French Revolution gave a long-lasting identity to the idea, already present in the British parliament, of grouping together like-minded parties and factions by arranging them to face each other. Exactly like an 18th-century unit of fusiliers would align to shoot a volley at an enemy unit.

Your relationship to progress within modernity defined your position relative to the president (the one who sits in front), the locus of liberal social compromise, the middle ground.

These days, the epitome of such logic has entered popular culture through the infamous political compass, which shows the limit of this reductionist way of thinking through an endless barrage of contradictions laid out on the four quadrants. Many educated, terminally opinionated Leftists will tell you how the Political Compass is part of the problem because it reduces the complexity of politics to a two-dimensional space when, in reality, it is much more complex.

Probably, in their minds, the solution is to keep politics discursive rather than systematic, and yet, they employ plenty of geometrical jargon without realizing the intrinsic contradiction. If you want to handle complexity through geometric tools, you need to learn how to do math in n-dimensional spaces, and you will realize that's very tedious. In addition, it eerily resembles the underlying logic of word embeddings, which are a foundation of the same LLMs currently disorganizing the infosphere. I'm not sure that's the way to go.

This restriction of thought and possibilities dictated by geometric and military language is a core factor serving the Manichean status quo. It follows that a transition to Augustian politics must come with reflection on the categories we employ to perceive ourselves in relation to others. Geometry does have a place in Augustinian politics, because sometimes, some systemic relations are easy to articulate on a flat surface, but it cannot be the primary and dominant language.

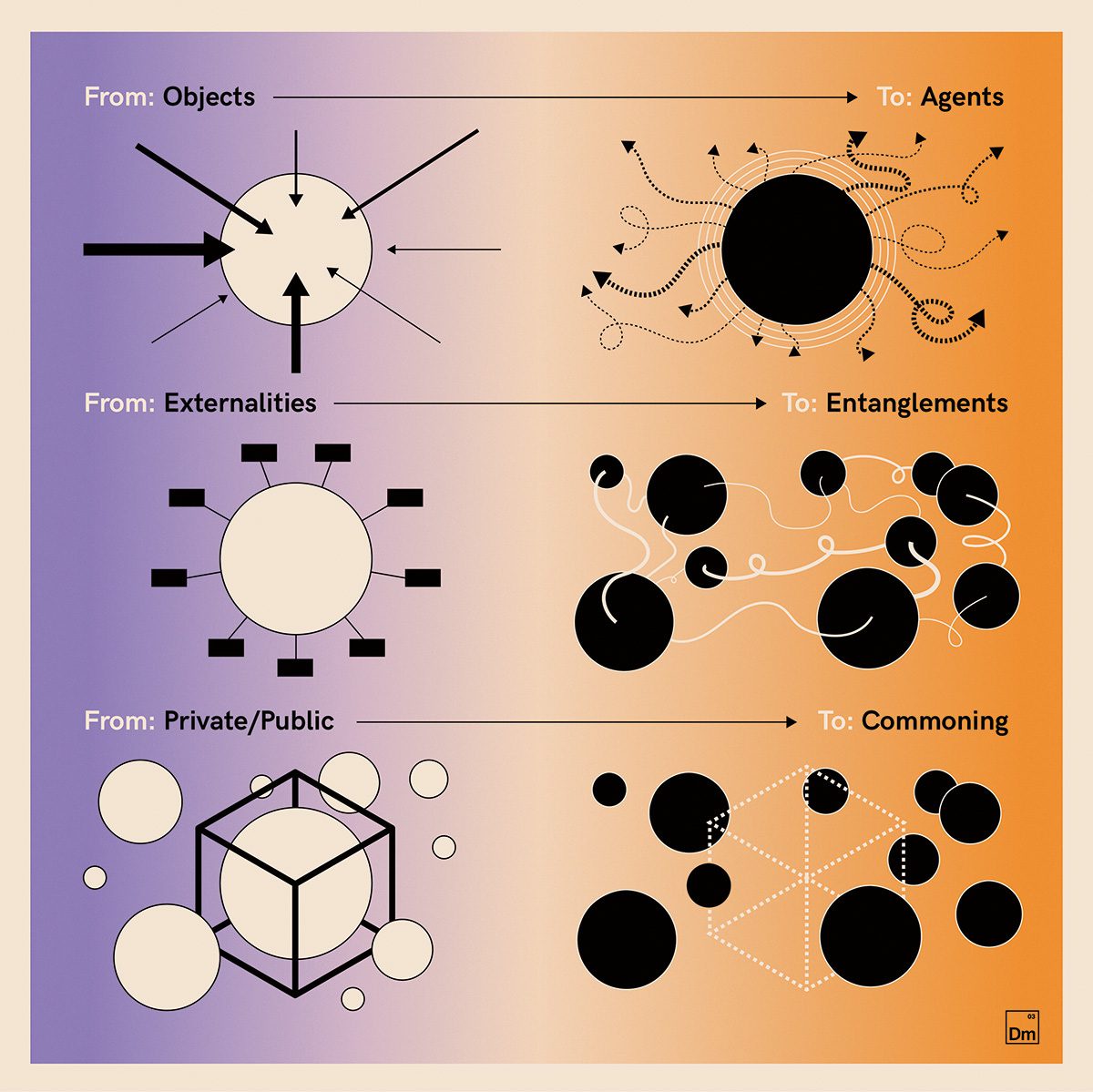

What's the alternative then? Following the Nunensian principle of “politics must be played with the full deck of cards”, a plurality of languages must be employed depending on the needs. In my personal experience, a useful starting point is to perceive yourself, your organization, and other entities in your political ecosystem, not in terms of “where” they are, but in terms of the change they can produce. The focus is neither on the actor nor on its position, which is fundamental in Manichean politics, but on the action, the force for or against change that they embody.

The outcome is what matters, regardless of the identity, ideas, practices, and narratives of the actors, which are relevant only insofar as they provide information to estimate the likelihood of our desired outcome and what role such actors might play in this dynamic or what decisions they are going to take.

More often than not, people we perceive as allies do not have the power or intent to create the change they say they want to create. Sometimes, people we perceive as enemies can be nudged into creating the same change we want. Napoleon, despite being a very geometrypilled dude, supposedly said: “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

Such a shift of frame opens up an array of possibilities inconceivable under Manichean politics, where you had to endlessly make sure to align identity, values, analysis, and actions among all the parties involved in an intentional and explicit collaboration, to make sure the morally good front was compact against the morally evil front.

Within the Augustinian frame, the vocabulary then moves towards the semantic space of systems, arguably a process already ongoing for almost a century. Tensions, tendencies, feedback, signals, noise, dependencies, domains, functions, diversification, variance, infrastructure, affordances, protocols: these are all terms we will have to master in our journey away from the geometric monoculture.

I want to point to another aspect of rupture between traditional Manichean politics and the Augustinian frame. Nunes presents the construction of social order as an endless endeavor because chaos will always try to seep in and disorganize society. The best we can do is to create an order that lasts long enough, is liberating enough, and feeds on an energy source that is abundant and exploitable without consequence for living beings (the Sun?). The result is a rejection of narratives revolving around any utopian conclusion of political struggle and an open-ended, always-demanding struggle against chaos. Coherent with this idea of politics without closure, this article won't have a conclusion.

-

@evan Well I'm a bit more motivated now, keep an eye out for future updates!

Either way, my pleasure, glad you're enjoying it, and some of the other ones that I've made!

-

@oglaf best survivorship bias comic ever.

Post suggeriti

-

War, Saint Augustin, Geometry, Rodrigo Nunes, and the new grammar of politics

Watching Ignoring Scheduled Pinned Locked Moved Uncategorized 7

0 Votes1 Posts0 Views

7

0 Votes1 Posts0 Views -

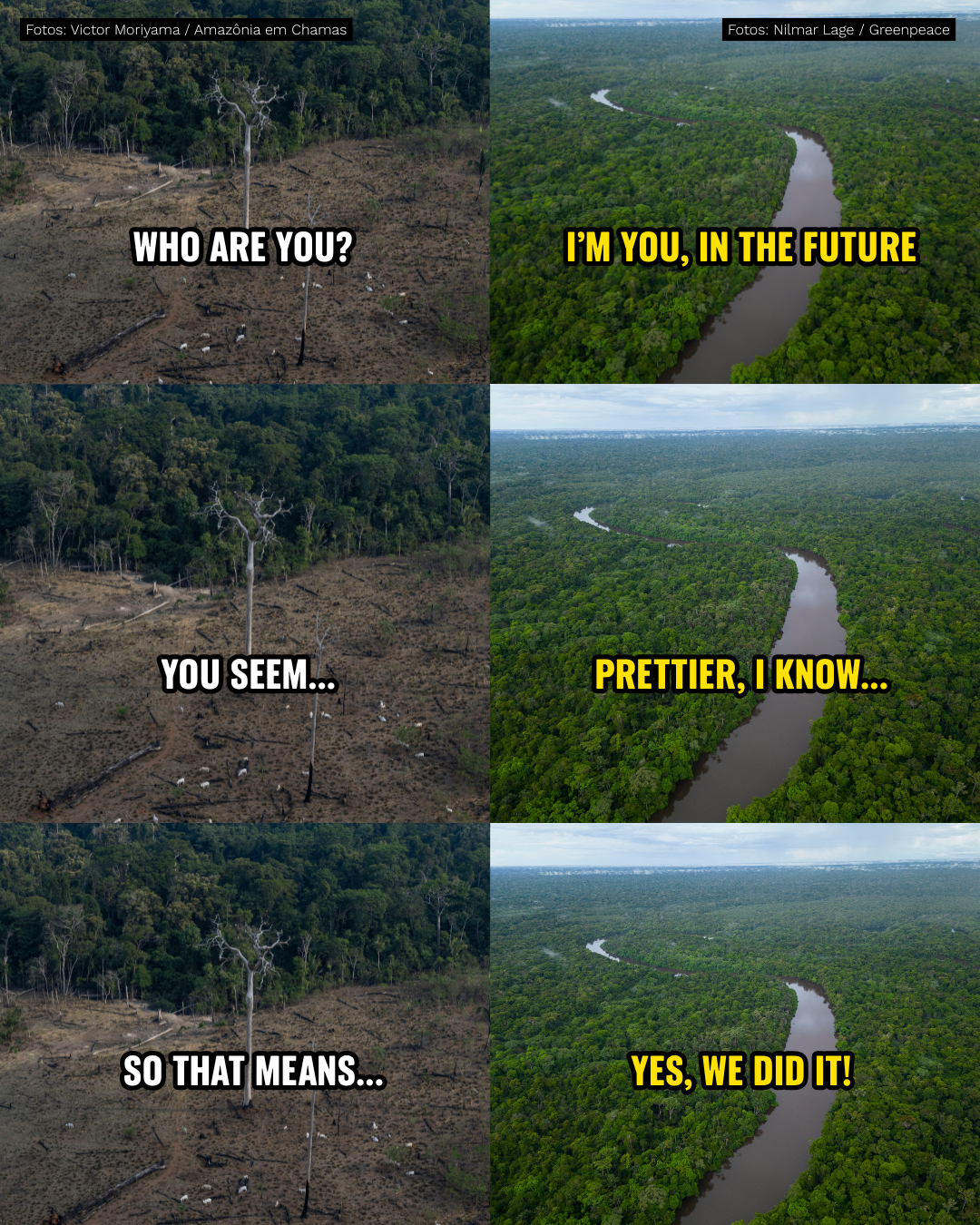

A safer future is possible.

Watching Ignoring Scheduled Pinned Locked Moved Uncategorized cop30 1

0 Votes1 Posts1 Views

1

0 Votes1 Posts1 Views -

56 years on this planet now.

Watching Ignoring Scheduled Pinned Locked Moved Uncategorized0 Votes1 Posts1 Views -

#AskFedi does any of you have an idea of what this chip is?

Watching Ignoring Scheduled Pinned Locked Moved Uncategorized askfedi1

0 Votes12 Posts17 Views