The museum where extinct creatures move again

Uncategorized

1

Posts

1

Posters

12

Views

-

The museum where extinct creatures move again.

At Shanghai’s Natural History Museum, using high precision projectors and depth tracking systems, researchers overlay moving imagery directly onto real fossil frames and walls. This creates the illusion of dinosaurs walking, ancient birds fluttering, and long extinct creatures shifting back into motion.

#globalmuseum #museums -

undefined stefano_zan@mastodon.uno shared this topic on

undefined stefano_zan@mastodon.uno shared this topic on

Gli ultimi otto messaggi ricevuti dalla Federazione

Post suggeriti

-

-

-

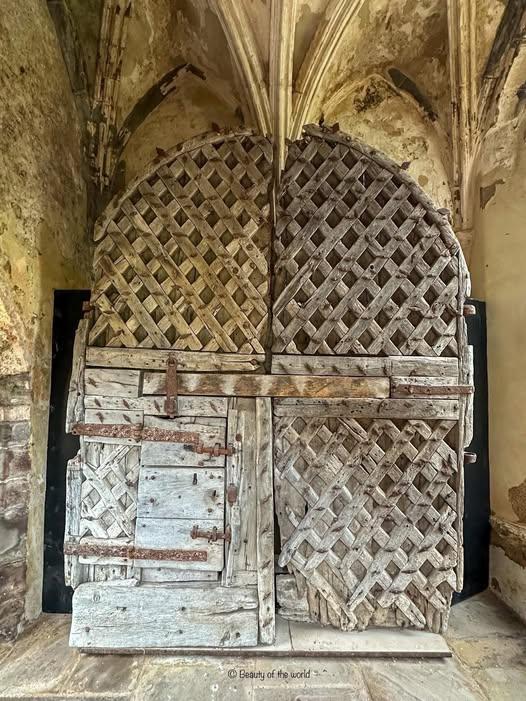

Chepstow Castle in Chepstow, Monmouthshire, Wales is home to one of the oldest surviving castle doors in Europe.

Uncategorized 1

1

-

National Museum of Korea had a #cosplay contest: Dress Like a Museum Exhibit 2025 My two favorites are this (famous magpies and tiger painting) and see next

Uncategorized 1

1